The First Inhabitants of the Coastal Valley

The history of Mevagissey as a significant human inhabitation begins long before the location had a name we would recognise. Settlers who had travelled West across the Mediterranean from north-western Italy found favour in a valley during the Bronze Age and decided to occupy the area. Marseilles, a Greek merchant, explored Cornwall in the late Bronze Age and described the inhabitants as skilled wheat farmers, usually peaceable, but formidable in war when they used horse-drawn chariots. He also described the Cornish trade in tin with the Mediterranean. The traces of the Bronze Age around Mevagissey are sparse, but their burial mounds can still be seen on the cliffs to the south of the village, and the hill fort ruins on Camp Hill remind us of their presence at this time. There was access by road to the Bronze Age port of Percuil, and when the Roman’s arrived at approximately the time of Jesus, they established a fort called Colonia using the old Bronze Age tracks.

The Arrival of Saints

In the first centuries after the roman’s left Cornwall in the 5th Century, the age of antiquity faded out and the middle ages began. For Cornwall and Mevagissey, this meant celtic traditions and a new wave of Christianity; a time that became known as the age of the saints. Mevagissey had two distinct settlements, Lammorick and Porthhilly, a fishing community. A saint from Ireland called Mevan arrived in the 6th century with recruits (including Saint Issey) from Brittany to convert the Cornish. In memory of those two saints, a church united the two settlements and the village became ‘Mevan hag Ysaye’ and eventually, Mevagissey.

The Norman Invasion

For a long time the most powerful priests and land owners were Cornish. Up until 875 Cornwall had its own King, though he may have been an underking, as we known the King of Wessex went hunting in Cornwall at the time. King Donyarth, the last Cornish King, supposedly drowned or was decapitated and had his head thrown into the river Fowey. At the beginning of the first millenium, the Viking king Sweyn Forkbeard conquered Wessex, but allowed Cornwall, Scotland and Wales to self-rule in exchange for making payments to the King. When he lost power, so did Cornwall and not much later the Norman Aristocracy carved out the land. After Norman invasion the Domesday Survey of 1086-88 informs us that Mevagissey was split into four manors. Porthhilly, Treleaven, Bodrugan and Penwarne. In this time there were strong trading links to mainland Europe, which were lost in the the hundred year war, but reestablished after it ended. During that time the first stone harbour was built. The people of Mevagissey have always had a strong dependency on the fishing industry, meaning that ecological changes and political restrictions on trade heavily impact the community.

War and Pilchard

Two years after the end of the hundred-year war, the War of the Roses began. Most families around Mevagissey were not actively involved, but Sir Henry Bodrugan of Bodrugan Castle kept his own private army and supported the House of York. His ship used to sail from Mevagissey and seize Dutch, Spanish and French vessels, and he made armed raids of his neighbours who supported the Lancastrian cause, stealing women, various goods and cattle. When Bodrugan supported Richard 3rd, who was defeated, Henry VII accused Bodrugan of treason, but Bodrugan was safe within the walls of his heavily fortified castle. Supporting Lamber Sminel the pretender was a step too far for Henry VII, and he issued Bodrugan’s death warrant. Bodrugan had made plenty of powerful enemies, and a local force (likely composed of some of the men of Mevagissey) arrived at his castle to execute him. As the soldiers arrived, Sir Henry supposedly fled, lept from a cliff and swam to an escape boat to take him to Ireland where he owned land. The title of Baron was stripped from his family after his death, and his castle destroyed. Mevagissey became a more peaceful place for the century.

Then, in 1588 the Spanish sent 130 ships to England. In response to this threat, the grandson of the man who had lead the attack on Henry Bodrugan made sure the people of Mevagissey were trained in arms and a beacon was kept ready.

By 1640, Mevagissey had a flourishing fishing fleat, these caught pilchard in summer, herring in winter, and mackerel in spring. The industry was thriving, but would have experienced a hull in the Civil War when the men of Mevagissey had to fight against one another, on whichever side the families they worked for were on. There was one battle in the Pentewan area.

When the royalists were defeated, the Puritans sacked the Church of England vicar, sold the church bells and knocked down the tower. This event inspired a poem from local royalists:

“Ye men of Porthhilly, why were ye so silly

In having so little power

You sold every bell, as Gorran men tell

For money to pull down your tower”

Smugglers and Methodists

In 1733 fishing was no longer turned to as the sole means of putting bread on the table. Smuggling was rife. The port at Roscoff was the primary stop, where french cognac, dutch gin, tea, tobacco, silks and lace could be picked up and brought back to be sold at high prices. However, when John Wesely came in 1750, the Methodist preacher had a radical impact on the people of Mevagissey, and some stopped smuggling. One man had made £3000 on his last trip, a sum equivalent to £175,000 in 2017, and decided to quit because he could not reconcile smuggling with Methodism.

Wesley Visits Mevagissey

One lady from Mevagissey who had heard Welsey preach near Mevagissey sent him the following letter:

“Sir, if at any time you be nigh unto Mevagissie, I shd. esteem it a great favour if you wod. Come and preach to the people, for in this town, there is much licence and drunkenness. The souls of the people cry out for a lead away from their sin, but the Church gives it not to them. Therefore, like sheep without a shephered, they stray from the true ways of godliness, and are in great need of salvation.”

Wesely wrote in his journal:

“We were invited to Mevagisey, a small town on the south sea. As soon as we entered the town, many ran together, crying, “see the methodees come”. But they only gaped and stared, so that we retired unmolested to the house I was to preach at, a mile from the town.

Many serious people were waiting for us, but most of them deeply ignorant. Whilst I was showing them the First principles of Christianity, many of the rabble from the town came up. They looked as feirce as lions, but in a few minutes changed their countenance and stood still. Towards the close, some bagan to lauggh and talk and grew more boisterous after I had concluded. But I walked straight through thew midst of them and took horse without interuption”

A later entry in Wesley’s diary indicates that his preaching had a significant impact:

“I rode to Mevagissey. When I was there last, we had no place in the town. I could preach only half a mile from it. But things have altered now. I preached just over the town to almost all the inhabitants and all were as still as night”.

Around this time there was an attempt to turn Mevagissey into a spa town, using the sulfurous springs in the valley. A Greek-style temple was constructed, but the project failed and the iron heating the spring was later mined.

Cholera Outbreak & Fishing Developments

In 1775 there was a successful application for a new harbour, and in 1866 it was enlarged. Around this time there was a Cholera outbreak which killed many locals. People moved out of Mevagissey in this time to places with cleaner water sources. The problem was solved in part because the locals enjoyed tea (and thus boiled their water).

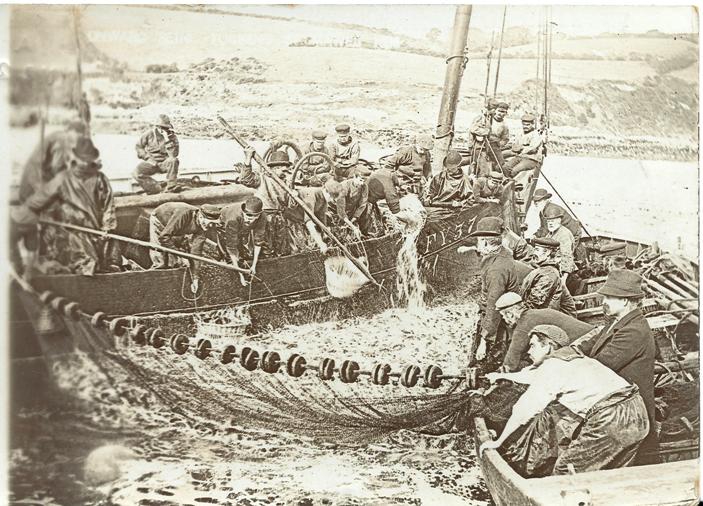

Over the nineteenth century the fishing industry changed. Drift fishing was found to be more effective, and pilchards were caught in great numbers. It is thought that this over-fishing may have been part of the reason for the decimated pilchard stocks.

Mevagissey was badly affected by the Great Blizzard of 1888. Farmers found cows frozen solid in fields, Mevagissey was completely cut off and houses were buried deep in snow. To explore Mevagissey through fiction in the Great Blizzard of 1888, check out this Mevagissey time travel story.

WW1 To Today

In 1914-18 German boats came in close in to torpedo merchantmen and sometimes fishermen. In both World Wars, fit young men left to fight leaving only boys and old men to fish, damaging industry. But today, the fishing industry is still alive and active, and Mevagissey is unique in that it is managing to grab the attention of the younger generations, who are still actively fishing from the shores.

Bodrugan’s castle is nowhere to be seen. The temple spa of Mevagissey remained the dream of some architect and never was. The wealth that flowed through the town from smuggling has flowed right back out again. The Pilchard no longer fill the waters and the permanent stench of fish no longer lingers in the streets. If you decide to take a boat trip from Mevagissey, you’ll be pleased to know you needn’t fear canon fire from Spanish ships – but despite all these changes, the fishing industry is alive in Mevagissey. You might say the history of Mevagissey is built upon pile after pile of fish.

The History of Industry in Mevagissey

If you visited Mevagissey at any point in the last several hundred years, your nostrils would be filled with the overwhelming stench of fish. Mevagissey was born and raised on fishing. The village would originally have been settled for its sheltered cove just a short distance from deep water. Since those early settlers, Mevagissey’s history has been a tale of an uncommonly resilient village that dozens of tough generations have kept alive through war, disease, international fame, hunger and a few bottles of smuggled cognac here and there…

Tellingly, the original Harbour Trust documents from 1774 were bound not with leather from cows, but from Ling skin, a fish in the cod family, which is five times stronger than standard leather. If you stop for an ale in the Ship Inn, you’re in the same space the first meetings took place. You can imagine men scribbling in fish-skin books, discussing rules to give sailors, traders, tourists and fisherman fair usage of the harbour.

Mevagissey Harbour Trust is unique in that it purchased the seabed from the Dutchy, so Mevagissey’s industry has a special feeling of independence.

Fish Species

Over 23 species of fish are targeted out of Mevagissey, as well as crustaceans like lobster and spider crab. The founding and growth of Mevagissey has always been centered around fish and the sea. However, towards the end of the nineteenth century, Mevagissey was recognised by Parliament for its significant involvement in trading tin, wine, tobacco, stone, cider ropes, hemp, flour and other goods.

It’s for good reason that the word most associated with Mevagissey’s history is ‘pilchard’. This one catch was what lead to the dramatic growth in industry, mostly from selling the oily fish to the Europeans, who craved Pilchard far more than the British. Oil from Pilchard was also used in street lamps in London, as this old poem attests. The poem describes how pilchard oil fuelled the street lamps that lit up the faces of London prostitutes and revealed if they had syphilis.

Pilchards! whose bodies yield the fragrant oil,

And makes the London lamps at midnight smile;

Which lamps, wide spreading salutary light,

Beam on the Wandering Beauties of the night,

And show each gentle youth their cheeks’ deep roses,

And tell him, whether they have eyes and noses.

Mevagissey’s Economy

In the early 20th century, approximately 75 million pilchard were exported annually. The pilchard shoals were so large that Killer Whales (called ‘grampus’ by the locals) were occasionally spotted venturing into Cornish waters for a good feed, a sight unheard of in recent times. It was the buoyancy of the fishing industry that helped Mevaigissey survive a loss of 6% of its population in the earlier cholera outbreak and through war time.

Despite a successful fishing industry and the significant amounts of money that have flowed through Mevagissey, it’s also known very difficult economic times. The streets were known for being sprawled with fish guts, which would have been made worse by narrow streets that weren’t fit for the scale of the movement of fish, (locals compensated for this by having exceptionally tidy houses). Horses couldn’t fit, so men had to carry massive quantities of fish through the streets.

After the world wars, when a generation of fishermen never returned home, the industry clung on with the hands of old men and young boys and in the 1960’s, you could see children scraping their fingers along pilchard barrels to snack on the left over oil. A common complaint was stomach ache caused by a limited diet consisting mainly of pilchard.

Women processed the fish, which were first salted in brine and then packaged. Special poles with weights were used to press firmly into the pilchard to squeeze more in to each unit before the lid was put on and at the time of writing this, one of the press holes can be viewed in a private car park near the Model Railway Museum.

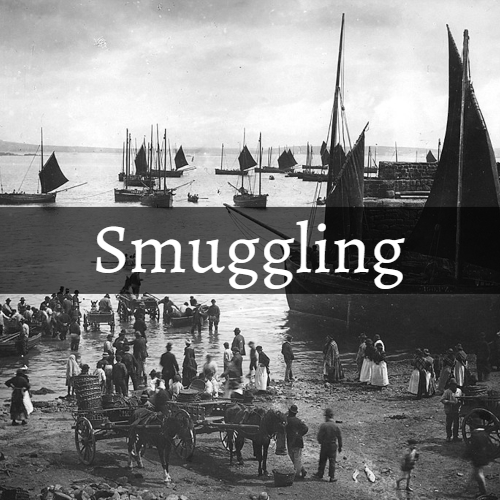

Mevagissey Smuggling

Mevagissey has numerous secret passages, trap doors and creative ways of getting through the village unseen to support Mevagissey’s underground industry: smuggling. Smuggling could be an extremely profitable enterprise, and as the government increased and enforced taxes more seriously, many began to run illegal branches to their businesses. Often this didn’t involve actively beginning to smuggle, but merely not paying new taxes as they were invented.

By 1733, smuggling was popular, with the primary stop being Roscoff. French cognac, dutch gin, tea, tobacco, silks and lace could be picked up and brought back to be sold at high prices. A single trip could make about £170,000 in profit in today’s money (2017). My Great Great Grandfather was a captain out of Charlestown, and he used to throw a few casual barrels of smuggled goods over board of his ship to roll in to shore with the tide, but that was in more recent years. When Mevagissey’s top boat builder agreed to build a boat as fast as the smugglers vessels for the enforcement officers, the people protested by ceasing to buy any boats from him. Taxes would have seem particularly outrageous given that Cornwall at the time was very cut off from the rest of Britain (in part by such narrow, winding roads, many of which being old Bronze Age tracks), and so taxes might have felt like they were being created by some up country aliens.

Explore further with this History of Mevagissey ebook from Amazon.

1970’s to Today

Today, Mevagissey’s fishing industry is alive and still producing fish for international shipping. A common difficulty for fishing villages is a lack of young people filling in roles as the older generation retire, but Mevagissey doesn’t have this problem, and there are lots of young people entering the industry. The charm of the village and its close proximity to The Lost Gardens of Heligan and other attractions makes it popular with tourists, which has become the dominant industry in Mevagissey.

You can read about Mevagissey harbour and angling here, or explore things to do in Mevagissey.

.jpg)